Food and body expert calls for “more practitioner training” as ARFID cases in children rise

- H W

- May 14, 2025

- 3 min read

Speaking to Victoria Kleinsman, who specialises in ‘Food freedom and body love says, “One of the biggest gaps (in ARFID) is education. ARFID is still widely misunderstood, even among professionals, so I’d love to see more practitioner training that goes beyond just meal plans and weight tracking. ARFID isn’t about stubbornness or defiance, it’s about fear, sensory overload, trauma, or anxiety.”

On January 26th, it was reported that ARFID cases in children had risen to a new high in the UK. This is a result of “extreme food avoidance due to sensory sensitivities, fear of choking/vomiting, or a general lack of interest in eating.”

ARFID is an eating disorder that stands for avoidant restrictive food intake disorder.

According to Beat Eating Disorders, it is a condition characterised by the person avoiding certain foods or types of food, having restricted intake in terms of overall amount eaten, or both. It can be found in children, teenagers, and adults.

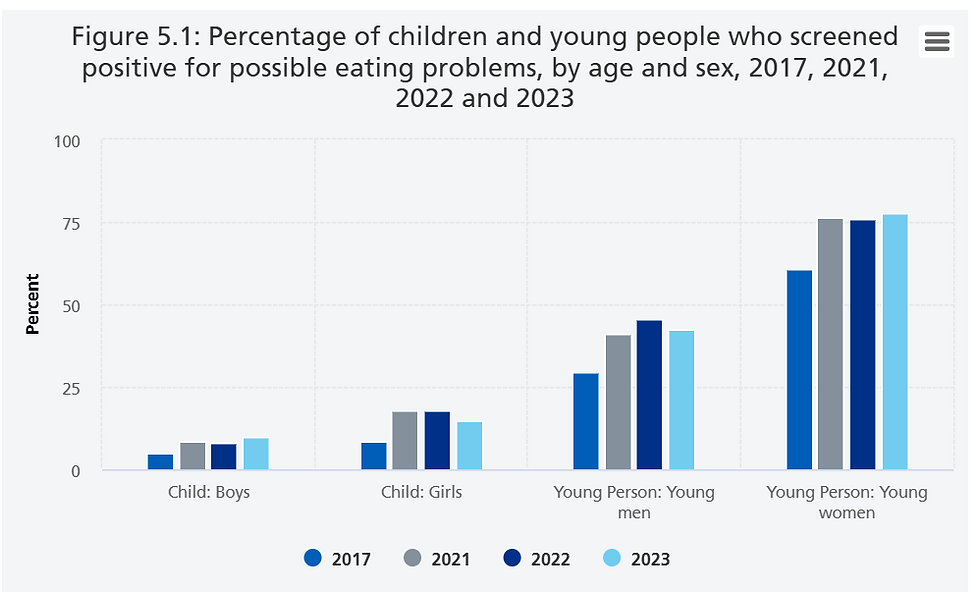

In 2017, the percentage of boys and girls aged 11-16, 13.5% screened positive for possible eating problems. This gained an 11.2% increase in 2023, resulting in 27.7%.

Eating disorder expert, Victoria Kleinsman, said, “Unlike anorexia, ARFID isn’t driven by body image concerns or a fear of weight gain. It’s more about extreme food avoidance due to sensory sensitivities, fear of choking/vomiting, or a general lack of interest in eating. In children, it can be harder to treat because their limited diet can quickly impact growth and development, and they may not recognize their eating as a problem in the way someone with anorexia might.

“A big part of helping someone with ARFID is understanding that their food avoidance is rooted in genuine fear, not stubbornness. Instead of forcing or pressuring food, the focus is on exploring the fear itself, whether it’s sensory-based, tied to a past choking experience, or simply an anxiety-driven aversion. By addressing the fear first, we can work on expanding food variety in a way that feels safe and builds trust, rather than triggering more avoidance.”

Kleinsman continues, “ARFID can affect a child’s development as it can lead to nutrient deficiencies, stunted growth, and social challenges around food. Early intervention is key because the longer restrictive eating patterns continue, the harder they are to shift. Helping a child build a positive and stress-free relationship with food early on can prevent long-term health and emotional struggles.

“We also need more nuanced treatment that focuses less on external pressure to eat and more on creating emotional and nervous system safety. For many people, ARFID treatment works best when it’s not about “fixing the food” first, but instead gently exploring why certain foods feel unsafe or unmanageable. Including occupational therapy, sensory regulation, and trauma-informed care would be a huge step forward.

“Support for parents is essential because ARFID can feel isolating and stressful to navigate. Some clinics now offer family-based approaches adapted for ARFID (FBT-ARFID), which can be really helpful. There are also great books, like Helping Your Child with Extreme Picky Eating, that give parents tools to support without pressure.

“I always encourage parents to focus on building trust over time, offering low-pressure exposure to new foods, and celebrating progress even if it’s small. And connecting with other parents going through the same thing, whether online or in support groups, can make a big difference, too.”

Comments